The learning community

The learning community refers to the impact of the wider community on teaching and learning. These could be friends and family of students, who have interesting life stories, or professionals who are engaged in the public understanding of their subjects.

It is said that “It takes a whole village to raise a child.”

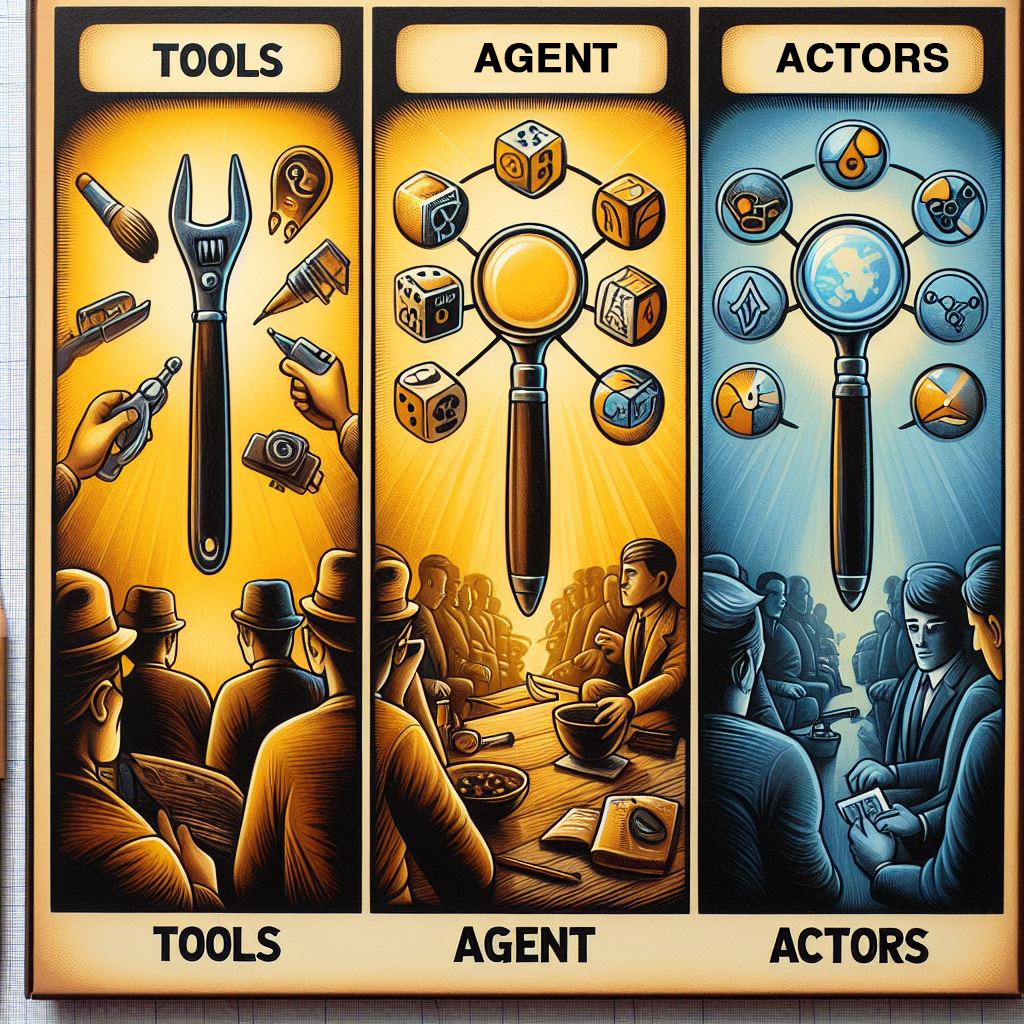

To see how AI might be a useful part of the learning community, we need to ask whether AI is a tool or an agent or an actor.

A tool is a machine that does a job for us, like a sat nav that gives us directions to our destination.

An agent has a greater level of autonomy. If the sat nav monitors traffic in real time and recommends alternative routes to avoid traffic delays, then it is showing some level of agency.

An actor shows the greatest degree of autonomy and independence. If AI says that a friend has not left their house for three days and has not made any contact with anyone else, and asks if you want to visit, then it is being an actor – a digital personal assistant. Especially, if it then makes arrangements for the trip, including booking a hotel room.

An actor does not have be a human influence. The French sociologist, Bruno Latour defines non-human activities as actors as long as they influence social situations.

At present, AI is being a tool for most of the uses discussed in these articles. Thinking tools are useful, as long as they do not prevent people from thinking for themselves. More sophisticated uses of AI, such as being a study buddy, may allow the AI some degree of agency to direct the learning.

Future developments in AI might facilitate the development of a device that acts like a personal tutor. The news that Microsoft is patenting a technology to offer an “AI-powered emotional management system” as part of an emotion-centred journaling feature, suggests AI might become a motivating actor sooner than we thought.

The AI and Education post: Enhancing Counselling Education Through AI: A Progressive Approach presents an AI application that develops the counselling skills of mature students who “role-play both counsellor and client, developing empathy and counselling techniques. ‘Call Annie'[an AI bot] offers face-to-face interaction via video calls”. Some students like the system so much that they are using the application as a “a virtual therapist”.

These are early days for the project and it is likely that the application is acting as a training tool with some levels of agency. More sophisticated iterations in the future might become so autonomous that they become social actors.

Throughout these articles we have stressed that pre-training AI is the best control teachers have to ensure that its use is productive and safe. This also applies to actor-level uses of AI.

The wider discussion for society is whether we want to enter such intimate relationships with machines, given the risks of psychological or emotional dependence. Many of us can become addicted to our screens. For others, it extends possibilities and horizons in the most extraordinary of ways.

| Q. This article considers whether we, as teachers or as members of society, should draw boundaries to limit the possible uses of AI in education. Where do you think the boundaries should be drawn? |

Updated 16/01/24 to include end of article question.